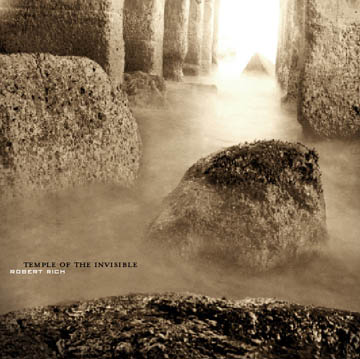

Temple of the Invisible

Temple of the Invisible finds Robert Rich at his most organic, eschewing the trappings of modernity or stylistic boundaries. Using only simple acoustic instruments, Rich has crafted a document from a distant time and place, a lost culture with musical underpinnings that reach from Java to North Africa, from Medieval Europe to the Tibetan Plateau. Rich uses the music of this unknown civilization as a platform to express an intensely personal quest.

Each piece documents part of a lost ritual, with mythical and spiritual components conveyed through a strangely familiar yet foreign musical language, as if unearthed from an ancient common ancestry.

Contributors include Sukhawat Ali Khan (son of the great Indian vocalist Salamat Ali Khan), Paul Hanson (from Bela Fleck & Flecktones, Wayne Shorter, Zenith Patrol), Percy Howard (from Meridiem, Bill Laswell), and noted solo artists Forrest Fang and Tom Heasley, adding dimension and power to this mysterious world out of time.

Instruments:

Robert Rich: prepared piano, mallet kalimba, flutes, percussion,

zithers

Sukhawat Ali Khan: voice

Forrest Fang: baglama, gu zheng

Paul Hanson: bombard, bassoon

Tom Heasley: voice, conch

Percy Howard: voice

Here is an excerpt of an article about Temple of the Invisible by Derk Richardson, for the San Francisco Chronicle's SF Gate website. You can read the entire article and the interview that preceded it on the "Interviews" page of this website.

Brave New World

The new world music of Bill

Frisell and Robert Rich

by Derk Richardson, special to SF Gate

Thursday,

May 1, 2003

If the world didn't change completely after Sept. 11, it certainly did get smaller. More people on planet Earth are sensitized to one another's existence than ever more. Unfortunately, heightened awareness doesn't necessarily translate into greater good will. In often fatal ways, cultural differences have grown more rigid and antagonistic.

Music has long been touted as a soothing antidote to savagery. And "world music," that unfortunate catchall for just about any ethnic artifact that's "foreign" to mainstream American ears, supposedly promotes cross-cultural understanding best of all.

But even as the neo-flamenco of the Gipsy Kings, the mourna of Cesaria Evora and the lilting Cuban melodies and rhythms of Buena Vista Social Club offshoots become a kind of hip Muzak at bookstore cafés and middle-class cocktail parties, I wonder how many insightful, let alone enduring, bridges are being built between the culture of the consumer and that of the artist.

Perhaps what's called for is a new kind of world music, one that truly represents an openhearted meeting of the minds from radically disparate cultures. The experiment has been ongoing in pop for decades, from projects by Ry Cooder, Paul Simon and Peter Gabriel through grassroots world-beat bands to today's multiculti dance-floor mixologists, but rarely has it reached the level of synthesis achieved in unique new recordings by jazz guitarist Bill Frisell and ambient soundscape musician Robert Rich.

(...edit...)

Musical Archeology

While the music on The Intercontinentals is self-explanatory, and Frisell's intention to cultivate connection across borders is fairly transparent, Robert Rich's Temple of the Invisible is harder to pin down. Rich's Web site describes the music as "a document from a distant time and place, a lost culture with musical underpinnings that reach from Java to North Africa, from Medieval Europe to the Tibetan Plateau," with each of the album's seven pieces further documenting "part of a lost ritual, with mythical and spiritual components conveyed through a strangely familiar yet foreign musical language, as if unearthed from an ancient common ancestry."

Playing flutes, zither, prepared piano, mallet kalimba and a variety of percussion, Rich recruited a mixed musical family of friends to join him on his journey: Sukhawat Ali Khan contributes impassioned Indian vocals; widely traveled virtuoso Paul Hanson plays bassoon and bombard (an obscure oboe-like reed); Forrest Fang plugs the bouzouki-like baglama and the ancient Chinese zither known as the gu zheng; Tom Heasley, known for his ambient tuba work, adds voice and conch shell; and Percy Howard, of Meridiem fame, deepens the textures with his post-operatic vocals. As with every Rich production, the attention to sonic detail gives new meaning to obsessiveness. Few studio technicians can match Rich's mastery of sound placement and the complex relationships between aural foreground and background, while keeping the focus on musical content. Temple of the Invisible sounds like nothing -- and a little bit of everything -- you've heard before.

"I've been interested in musical archeology for some time," Rich explained in a recent e-mail exchange, "often ponder what the music would have sounded like in vanished cultures. It makes me aware of the fragility of our own musical heritage. ... Also I have long loved the music of Harry Partch, which somehow invents a culture of its own.

"For years now I have been playing around with trying to assemble a small ensemble to invent music from pre-Hellenic cultures," he continues, "perhaps even pre-Sumerian Akkadian. Not exactly an archaeological forgery, it would be more like a question posed to history, projecting a 'possible' language into the past."

The project, Rich explained, would be called "Rites of the Bronze Age." But as it would take too long to realize, he scaled back to "trying to make a very personal music from my own vocabulary, which nevertheless sounds like it came from somewhere else ... By including the contributions of other musicians with mastery in some different styles, especially Sukhawat Ali Khan and Forrest Fang, I was able to pull the sound a bit away from my own personal vocabulary and give it a taste of authenticity."

Rich chose the instruments by imagining the sounds of his invented culture, consciously avoiding "some instruments that have too much of a specific cultural reference, or have become clichéd by recent 'world music' overuse, such as didgeridoo or gamelan." The players came individually to his studio in Mountain View and improvised on the tracks initially laid down by Rich, who then edited it all together, giving the resultant pieces titles from a made-up language, such as "Etranon," "Pa Tanak," "Fasanina" and "Lan Tiku."

"I have a vague libretto in my head," the composer/producer admits, "but I would rather leave it hidden, to allow other people to imagine their own stories."

All the World's Music

Creating one's own narrative from the limitless resources of the world's history, culture and imagination -- that's what connects the new world music of Rich and Frisell. "I agree with Lou Harrison that all music is 'world music,'" Rich explains, "and no music is pure. Yet calling something 'world music' is a bit like saying 'Mediterranean restaurant' -- it's meaningless and overgeneralized: Spanish, Moroccan, Provencal, Turkish food are all 'Mediterranean,' but very unique from each other. These general terms are convenient inventions for marketing novelty to Americans who don't want to take the time to understand the subtleties of other cultures.

"I think we each need to find personal approaches to digest the wonderful diversity of our polyglot society, especially as information and immigration bring widely different cultures into constant contact. My own approach is to digest as much as I can of the vocabularies that personally resonate with me, and somehow subconsciously integrate them into a personal voice."

In short, to paraphrase Wes "Scoop" Nisker, the trickster sage of '70s alternative radio newscasts and contemporary Western Buddhism, if you don't like the world music you're hearing, go out and make some of your own, or listen to someone who does.